President,

U.S. Epperson Underwriting Company

May 13, 1951

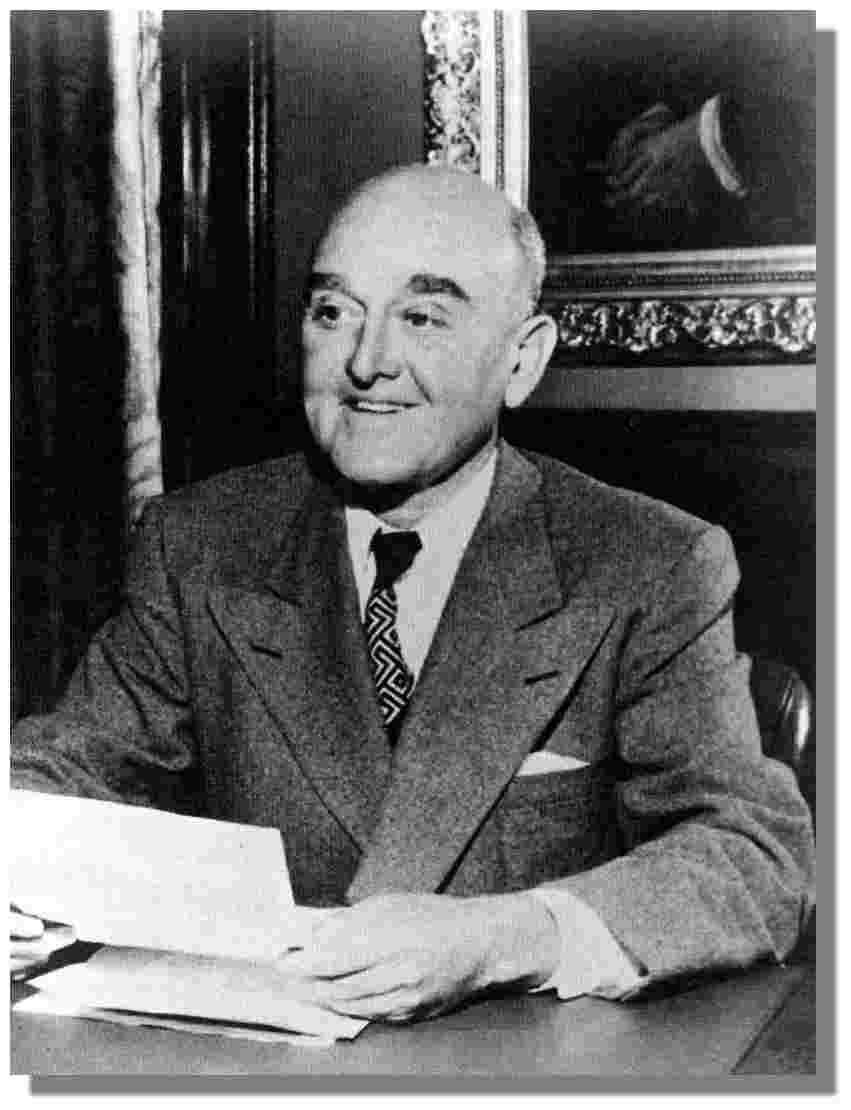

| James J. Lynn

President, U.S. Epperson Underwriting Company

May 13, 1951

|

|

At 9 o'clock on the morning of the ninth day of the ninth month in the year 1909 a homesick 17-year-old youth named Jimmy Lynn got off the train at the old Union Depot. Perhaps even then the something different in his nature was coming to the surface, something that caused him to notice the coincidence of the number 9.

Although the day was Sunday he walked across the railroad tracks to the Missouri Pacific office above the freight house. Men were working, so he went to work.

Some twelve years later the whole business community of Kansas City knew James J. Lynn, successor to U. S. Epperson and owner (with a huge debt) of the insurance underwriting company for a large share of the lumber industry. He stood out as a youthful prodigy.

This year, 1951, people who like the ring of the term "business empire" could put Mr. Lynn in the empire class, at least by Kansas City standards. It spreads into three separate insurance operations, into oil production, citrus fruits, railroading and a substantial banking interest. Financially the original Epperson enterprise is now overshadowed by oil but it is the largest reciprocal fire exchange in the world.

This man who pushes ahead building and expanding in the world of big business is unique. In one sense he suggests a mystic in Babylon, a man more concerned with a religious philosophy than any of the showy or luxurious things that money will buy.

LIFE CLOSE TO NATURE

His private office in the R. A. Long building breathes financial stability, a massive walnut office hung with heavy draperies in the manner of past decades. The bald man behind the heavy desk is bronzed from persistent living outdoors. Life close to nature is part of his creed. His face is so sensitive that you hardly notice the square jaw. There is nothing about him to suggest the bulldog type.

Here is no ordinary case of a man devoted to his church, serving on church boards and having the minister out for dinner. Mr. Lynn belongs to no church. Through his years of spiritual searching he attended many churches of many creeds.

The scope of his activities implies that he is one of the busiest executives in this part of the United States. From this intensely practical life he takes time for meditation, contemplates the meanings of humanity in the vast scheme of things. Out of these meditations and years of Bible reading and reading from other religions he has developed his own approach to the Christian philosophy. He discusses it freely, but not in a way that is easy for a visitor to understand. Superficially you can say it is wrapped up with the physical and mental side of daily living close to nature. To this writer it suggests a return to the simplicity of Christianity in earlier times when people worshipped in the forests. The exercises which he takes outdoors (breathing, tensing and relaxing exercises) may have been suggested by his reading of Oriental religions. This line of study started with a book by E. Stanley Jones, the famous missionary in Asia.

Most Kansas Citians have driven past the 100-acre Lynn estate which lies between Sixty-third street, Meyer boulevard, the Paseo and Prospect. For years people have mentioned it in connection with his 9-hole golf course. The golf course was abandoned some years ago. Beyond the fences and the shelter of dense foliage lies a forest and orchards and vineyards. This is James J. Lynn's outdoor retreat from early spring to late fall. He stays close to the orchards from the early flowering time to the season of harvest and glows over the opportunity to give away fruits. In the forest are some 2,000 fine hardwood trees which antedate the encroachment of Kansas City. Winters he spends all possible time in Southern California where he can continue to live outdoors.

This is the type of life Mr. Lynn manages to find in the midst of the business hurly burly. While he is nominally vacationing in California he dashes back and forth to business meetings and the large conventions of lumber men or automobile dealers, the men of the fields where he operates with insurance. His business for the lumber industry has multiplied itself many times to hold the rank of largest reciprocal fire exchange in any industry in the world. His somewhat similar type of reciprocal insurance for American motor car dealers is not far behind, and within the last eighteen months he launched a new stock company with full coverage for motor car owners. It approached the million- dollar mark its first year and appears to be going far beyond in 1951.

This man absorbed with things of the spirit is a very active oil man. His operations spread over some 25,000 acres of leases in Illinois, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. Financially oil is the biggest of his enterprises with a gross income from wells that now averages around 2 million dollars a year. In the Rio Grande valley of Texas he is a large grower of citrus fruits with 500 acres in grapefruit and orange groves. As the result of the freeze last January there will be no fruit from the area for two years. But in good times the income from 500 acres has run as high as a half million dollars in a year.

A railroad job brought him to Kansas City and he is a railroad man today, one of the small group of Mid-Westerners who moved to gain control of the Kansas City Southern and Louisiana and Arkansas railroads from eastern interests and to lodge the headquarters firmly in Kansas City. He is a banker, a very large stockholder and chairman of the executive committee of the Union National bank.

And this is the man spiritually akin to ancient prophets. Men of a slant only a shade different from his came out of the desert to denounce the splendour and wealth of Babylon.

The business rise of Jimmy Lynn is one of the sensational American success stories, yet different from most. From the beginning, his talents have been carried by a peculiarly sensitive human being, one who could never bear the thought of any man's ill will.

BOYHOOD IN THE SOUTH

He was born in 1892 near the crossroads village called Archibald, La. That long after the Civil war and reconstruction period the catastrophe still gripped the family.

Until Jimmy was 6 his father was a tenant farmer. Jesse W. Lynn, a neat man with a blond mustache, worked hard to make up for all that had been lost. In the war the family had lost all its lands and slaves. Grandfather Lynn had died from a wound received in the Confederate army. Jesse Lynn had never been given the chance, even for normal education.

Eventually the family came into possession of the 120-acre farm that had been salvaged by Jimmy's mother's family, the Archibalds. And that farm was held under a debt to the other heirs.

Jimmy, the fourth of six children, took his turn chopping and picking cotton, but he was the member of the family assigned to help his mother whenever she needed him. She was a dark-eyed little woman, packed with energy, Scotch Presbyterian and saving. Most of Mr. Lynn's memories of his parents are of the hours working by their side. There was seldom time for relaxation. He still gets pecans from the trees he and his mother set out on the farm.

His first reputation as a prodigy came at the age of 5. That was the year he went to the little log schoolhouse two miles away. He was too young to receive much attention from the teacher, so he memorized everything in the Blue Back speller.

One of the storekeepers at Archibald stood him on a cracker barrel to spell and give definitions to the amazement of the loafers. Anything in the book, big words like "incompatibility" and "incomprehensible" he spelled and rattled off the definitions.

"Well, I swan!" and "I'll be a salted dog!" said the wise men of the corner store crowd.

Later years he sat on the porch of this same store selling fruit from the farm. Butter, he delivered to regular customers who had no cows of their own.

A GOOD BALL PLAYER

His timidity and horror of causing displeasure may have helped his school record. He was shunted around from school to school, to whatever district could afford a teacher that year. And in each, the teacher pointed out Jimmy as the example of top class work and perfect deportment. He saved himself from the label of "teacher's pet" in baseball. The first game in which the Archibald boys were outfitted in regular baseball suits, they beat the older Mangham town school team 10 to 2. Jimmy scored four of the runs.

The years Jimmy Lynn worked for the Missouri Pacific railroad were unusual for one thing. When jobs were hard to get there was always a station agent who wanted him. He started at the Archibald station in school time, sweeping out and keeping the freight house in order for $2 a month. At fourteen and graduated from grammar school, he had a job at the Mangham railroad road station and made his board and room doing chores at his cousin's hotel.

His first life ambition was fixed on the glamorous office of division superintendent, a life goal that he never achieved. The most impressive figure he knew was W. C. Morse, the division superintendent. In a private car this stern but warm-hearted individual of knitted eyebrows traveled up and down the line. Whenever another station agent asked for Jimmy at higher wages, Morse grumbled that he was too young and always let him go.

That was the way he went to Oak Ridge for a temporary job at $35 a month. From there he moved on to Ferriday, the city and division point at a remarkable $65 a month. When there was a second opening he got the job for his older brother who married on the strength of it Slackening business forced a cut-back and Jimmy insisted that he was footloose and he was the one who should go. A traveling auditor for the road was quick to recommend him to a friend with the M. K. railroad at Moberly, Mo., and that turned out to be the high road to Kansas City.

Homesickness can be a terrible thing for anyone. More than most 'teen-agers, Lynn depended on the warmth and good feelings of human relations. At Moberly he was lost in a world of old people, old men at the office and two old women who rented him a room. One of these women struggled with belated music lessons and hammered away on the piano until all hours of the night. Then she resented Jimmy's alarm clock that went off early in the morning.

And so he found the job in Kansas City, working for the chief clerk to the Missouri Pacific division engineer. This chief clerk was a man he had known in Louisiana. From that Sunday arrival in Kansas City he felt that he was among friends. Within a little more than seven years he was to be the general manager of the big underwriting company, second only to U. S. Epperson himself.

HE CAUGHT ON FAST

Promotions came fast. He was employed on the Missouri Pacific in Kansas City as an assistant auditor. In less than a month the auditor was transferred and a frightened 17-year-old Jimmy Lynn, handled the auditor's job. He learned it by doing the work and after that he was not afraid of new jobs.

But the main theme of the seven years was education. He started from a public, school education that had been cut off in the middle of the ninth grade.

About a year and a half after he came to Kansas City his young assistant planted the idea of getting a legal education at the Kansas City school of law.

The law school exacted Jimmy Lynn's promise to make up the high school education that he had missed. He carried his full law school course and high school subjects at the same time. Within a year he added a correspondence course in accounting to the load--sopped up education in three different fields by night and held a full time job by day.

At 21, before he had completed his law course, he was admitted to the bar. By that time he had stepped up to an assistant in the firm of Smith & Brodie, certified public accountants.

Without such items as getting a high school education and going through law school, Jimmy Lynn's accounting education alone would have been a prodigious undertaking. Two local accountants offered night courses to the correspondence school students and Jimmy took them. On his own he read everything in accounting he could find and worked all the problems.

Under the rules of the state board nobody could become a certified public accountant before the age of 25. Long before that age Jimmy Lynn was handling involved, top bracket accounting jobs for Smith & Brodie. When he was 24 he passed the state examination with the highest grade on record to that time. Confronted with such evidence the board waived the age rule and gave him his C. P. A. certificate at 24. By that time he had a 20 per cent interest in the firm.

It was during this period of high pressure education that Jimmy Lynn met and courted Miss Freda Josephine Prill of Kansas City. They were married in October, 1913.

Along with the urge to please everybody Jimmy Lynn seems to have been born with unusual curiosity. It was in his nature to look for the explanations of everything. For a curious individual, accounting can be an exciting adventure. Figures tell the story of a business, how it operates and what makes it tick.

In Kansas City young Lynn was assigned to accounting work for the U. S. Epperson Underwriting company and the Lumbermen's Alliance which it served. In Chicago and St. Louis he audited other reciprocal insurance exchanges. The figures were business education.

TRAINING UNDER EPPERSON

Thousands of Kansas Citians in a younger generation have seen oil paintings of U. S. Epperson, the big, bald man of the dark mustache. In other years Kansas City knew him as the spirit of gaiety, the leader of the Epperson minstrels, the club man, good companion and the friend of visiting stage celebrities.

At his office he was all business, outwardly stern and given to unusual working habits. His day started around 4 in the afternoon and seldom ended until midnight. His thoroughness was a legend. When he started probing into a case of fire loss, he spent all night on it, refusing to give a thought to anything else.

There is an illustrative story of the night a scrub woman gathered up all the records of a case which he had spread out on the floor around him and Epperson neither heard nor saw. The next day there was a frantic search for the records. When somebody thought of asking the scrub woman she said, "Oh, yes, I gathered a lot of stuff off he floor--two sacks full."

Men from the office spent many hours in the city dump before most of the records were returned to the files.

Circumstances brought together the boyish Jimmy Lynn and the weighty Epperson. Lynn was assigned to audit the affairs of a burned-out Mississippi mill which happened to be a case that had particularly concerned U. S. Epperson. On the way to Mississippi, Lynn read Epperson's voluminous file and made a point of answering all the questions that had been raised. His audit revealed the clear motive for arson. Epperson showed that he was impressed. It happened at a critical time.

Death took H. A. Thomsen, the underwriting company's general manager, and Epperson was like a man who had just lost his right hand. He called on Lynn to straighten out some of his personal affairs, then offered him the job of treasurer in the company. Lynn refused.

Late at night, while he worked over the books in this office, Jimmy

Lynn felt Epperson's eyes on him. And from time to time he heard the words

"I wish you weren't so young."

BID FOR HIS TALENTS

Out of that situation came the offer of the top job of general manager. At the age of 24 and barely arrived at the status of C. P. A., Jimmy Lynn had the experience of competing powers bidding for him. Epperson started with an offer of $5,000 a year and worked it up to an arrangement that amounted to $12,000. The salary was so precedent-shaking that Lynn was sworn to secrecy and it has been a secret to this time.

Fred A. Smith, head of the accounting firm, countered by offering Lynn a full Partnership which was probably worth more than Epperson's $12,000.

It wasn't salary that tipped the scales but opportunity. Epperson spoke of his age and the chance to take full responsibility within a very few years. The opportunity turned out to be greater than Jimmy Lynn knew, and also far more precarious.

The hope of some day taking over full management for Epperson ended in 1921. Epperson decided to sell. He was ill and fearful that something would occur to destroy the value of his business. He wanted put his affairs in order.

A frantic Jimmy Lynn proposed that at he should buy the business himself. Epperson state the very obvious fact, "You don't have the money."

In his later years E. F. Swinney, head of the First National bank, talked about Jimmy Lynn as his No. 1 example of a risky loan that produced great results. Swinney elaborated with the enthusiasm of a man who might have been criticized or kidded for his daring.

The size of the loan which was the purchase price of the company has never been made public. It stood somewhere high in the hundreds of thousands and it was made strictly on the character of a young man who was not yet 30 years old. The notes were handled through the bank but it was generally understood that Swinney had personally guaranteed the loan.

When Lynn produced a check for the full amount of the purchase price, U. S. Epperson was so dumbfounded that he took a month to decide to accept the check and sign the contract.

The Epperson company had originated with a problem in the lumber industry. Because of the fire hazards at lumber mills in early years they were unable to get insurance for more than three-fourths their value and that only at exorbitant rates. In 1905 R. A. Long and other leaders of the industry organized the Lumbermen's Underwriting Alliance which was set up to spread the individual's risk throughout many companies in the industry, the group standing ready to make up the fire losses of any one. U. S. Epperson formed his company to handle the insurance for the alliance on a flat percentage basis. From the beginning it was a choosy arrangement in which the poor risks were not admitted to the alliance. Those who took the necessary steps to protect themselves against loss received full insurance at reasonable cost.

PROGRESS UNDER LYNN

In 1917, when Jimmy Lynn became the Epperson general manager the insurance premiums ran somewhere less than a million dollars a year and the resources of the Lumbermen's Underwriting Alliance were under a million. Today the annual premiums are around 6 million and the resources have grown to more than 13 million.

A period of rapid growth started immediately after Lynn bought the Epperson business. He attributed it to the talents of people in the organization. These talents were encouraged by his policy of turning people loose to show what they could do, a policy that also involved paying salaries according to demonstrated ability. As summed up by one man who was there at the time, it was a case of opening the door to individual opportunity.

The prodigious loan made by E. F. Swinney could have been paid in three or four years. Such were the profits from the stimulated business. When the loan was reduced to manageable size, Lynn chose to expand. The second year he moved into the field of reciprocal insurance for motor car dealers. They had formed their own universal Underwriters exchange which had $57,000 of premiums when Lynn took over the management. The exchange now has premiums of around 4 1/4 million dollars and it covers one-fourth of the factory authorized dealers of the country. Like the lumber companies, the automobile dealers come into their exchange on a highly selective basis that holds down the total.

The Lynn sideline in citrus fruits started back in 1927 with a 20-acre ranch. He discovered that he couldn't get top management for a ranch of that size so he expanded to 500 acres.

His oil business started in 1938 on the kind of deal he wouldn't take today. In the middle of a large Illinois field a stubborn farmer held out for $50,000 as the price of a lease on 100 acres. The big and experienced operators wouldn't take it. Lynn paid the $50,000 and got a dry hole for a start. The second drilling job produced one of the best wells in the field and he was on his way.

The only strictly public job accepted by James J. Lynn was service on the park board. It might have been connected in his mind with reverence for the outdoors and life close to nature.

After he had resigned from the board he had opportunity to sell the tract of land on Sixty-third street for an outdoor theater. It happened to be near the new Sixty-third street entrance of Swope park, so Mr. Lynn telephoned J. V. Lewis, park superintendent. Lewis had been saddened by the thought of a private business beside the new entrance.

"Well, the only way to make sure the park is protected is to put the land in the park," said Mr. Lynn. "I'm giving to the city."